Typical China's Blog

- Home

- Blog

- Customs & Culture

- Unique Hakka Architecture

Unique Hakka Architecture

- Sophie

- 7/19/2018

- Customs & Culture , Tulou

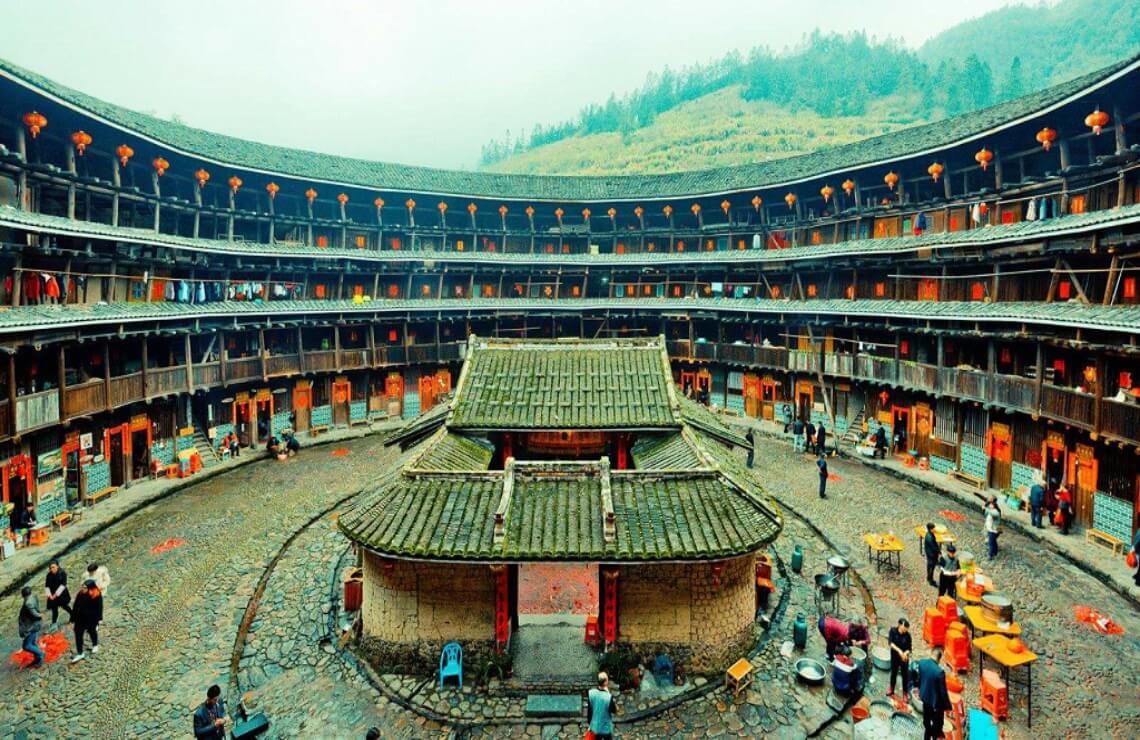

Most of the earthen buildings are circular, square, or phoenix-shaped. Others are oblong, or in the shape of Eight Trigrams, crescent-shaped, armchair-shaped, and so far. They are also variations on the same shape. They have all kinds of characteristics, but they also have a distinct commonality. In the Hakka language, the circular buildings are called “circular stockade villages.” From the words “stockade villages,” people can imagine how large they are. Of all the different shapes, the circular building is undoubtedly the one that gives people the greatest sense of mystery and singularity. Almost all of the circular buildings have only one main entrance. As soon as the main door is closed, the interior becomes a world of its own and everything outside is kept at bay. The two shutters of the entrance are thick and high, and are generally also covered with sheet iron: it’s almost as if two armored warriors are guarding the entrance. Children stand at the sides of the door and often exert all their strength and yet they cannot budge the door. How thick is the wall of the circular building? Just imagine that it is so thick that the top of the wall can accommodate a banquet table.

After you enter, you see the circular building’s hall. This is the passageway for going in and out of the whole building and it is also a public lounge. Generally, long wooden benches are placed on either side of the room; when people have nothing else to do, they can sit here and chat with one another. In quite a few halls, you’ll see hullers for rice and other grains, stone mils, and mortars for pounding cooked glutinous rice into paste. And so there is also this kind of scene: women pounding rice or milling flour, and making sound rich in rhythm, while the men chat about all kinds of subjects.

After you walk through hall, there are two verandas-one along either side, as if they are two long arms gathering all of the rooms, which are of the same size and shape, into a circle. On the first floor are the kitchens, with no windows to the outside, but there are windows facing in that have a vertical wooden dividing bar. These windows are generally wide open to let in light and fresh air. Below the window, there is usually a wooden cupboard where chickens and rabbits are raised. People may sit on top of it, so the cupboard has dual functions. The second floor functions as a storage area for food and farm tools. The bedrooms are on the third floor, and it is only beginning with the third floor that there are small strip-shaped windows.

In the circular buildings, there are at least two staircases, and generally there are four staircases for public use. They are set up symmetrically on the two sides of the axes in the entry hall. In Pinghe and Hua’an, although the circular buildings look similar, because there is not a connecting corridor upstairs, each family has its own staircase. The courtyard has at least one well: at the side of the well, women wash vegetables and do the laundry as they chat with one another. This is another animated spot.

On the first floor of the circular buildings, there is an ancestral hall in the open hall facing the entrance for sacrificing to the ancestors’ memorial tables. It is the place where the clan members worship the ancestors and discuss the business. If it is a relatively large circular building, sometimes there is an ancestral temple in the center of courtyard. The temple is square, with two halls, each having rooms on both sides. It serves as both a family temple and a clan “council,” and it can also serve as school. Some circular buildings also have a smaller circular dwelling within the large one. This creates another unusual scene inside.

Villages with circular buildings also always have square earthen buildings “four-cornered buildings.” Although the exterior appearance is entirely different, the interior of the square buildings isn’t much different from that of the circular ones.

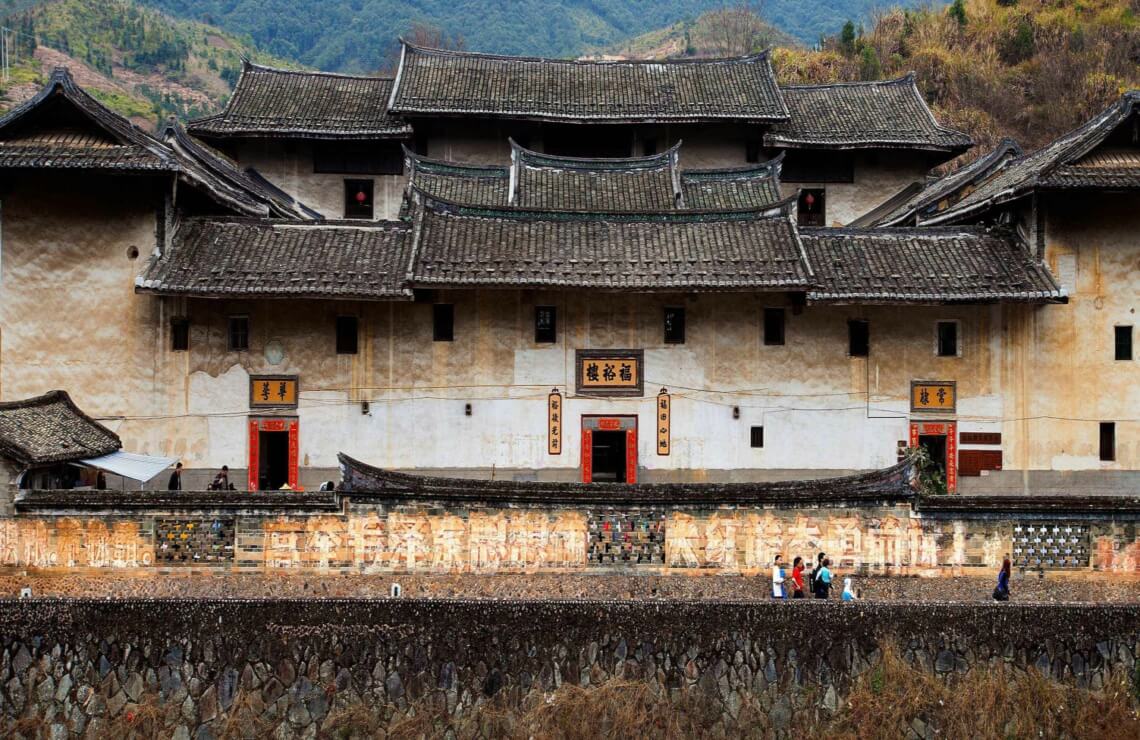

The phoenix building is another popular style. It has repeated layers of random heights. It looks like a mansion or a palace, and its interior is beautifully decorated. But in the southwestern Fujian villages, these buildings are the homes of ordinary farming families. So upon first walking into a phoenix building, few people can hide their surprise: how did it happen that in the past, mountain villages had luxurious homes like this? The phoenix buildings have three halls as the core of the central axis. The left and right sides are balanced with symmetrical rooms. The number and size of these wing rooms vary according to the owner’s resources. Each side may have one or two, or even three, rooms. The rooftop is gently low-pitched; the style is simple, yet impressive. It distinctly resembles Han dynasty palaces. The decorations on its ridges are even more exquisite and delicate. The upturned ends on either side are shaped like ox horns or phoenix or swallow tails. The framework of the ends of the ridges is made of cast pig iron covered with lime. The ridges of the entire roof are lacquered in colors. The drawings are of peacocks, phoenixes, and other auspicious animals, birds, and plants. They look almost like the ridges of palaces. In front of the phoenix building’s main entrance there is always a threshing ground, as well as a half-moon-shaped pond. The building is always lower in the front and higher in the back. The center party is high, the two sides low. Perhaps this sounds a little abstract. But if you look up at the ridge of the phoenix building, the eaves are upturned high in the air: isn’t this exactly like a phoenix spreading its wings in preparation for flight?

Comments